Dried Persimmon

Hoshigaki (Japan)

Certifications such as Geographical Indication can encourage consumers to explore the provenance of foods more deeply. Here, a dried persimmon from Ichida in Nagano Province (Japan) reveals the name of the producer to provide a more personal connection to the farmer. Hart Feuer

Hoshigaki is a form of dried fruit typical for East Asia, including China, Korea and Japan. Generally, hoshigaki are made from astringent persimmons, which are inedible unless allowed to become over-ripe. Harvesting the astringent persimmons when they are still hard and air-drying them was useful historically for a number of reasons:

(1) extend the season for consumption of persimmons; (2) take advantage of persimmon varieties that yielded high potential sugar content; and (3) find enjoyable uses for climate tolerant and adapted varieties of persimmon.

In short, persimmon drying allowed persimmon producers to maintain higher biodiversity and extend the season for persimmon consumption. Over the years, the artform of producing fruit, preparing, drying, and enhancing certain organoleptic characteristics has made hoshigaki into a noble heritage product.

Heritage Food Certifications:

– Geographical Indication (2016) – Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

– Regional Collective Trademark (2006) – Japan Patent Office

Comparable Certified Products

Noto Shika Koro-gaki

Provenance 1920. Unique features: discrete local variety (egg shaped), hand massaged.

Dojo Hachiya-gaki

Provenance early 18th Century. Unique features: discrete local variety, hand-cut, hand-massaged, swung to extract more sugar. Other certification: Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) – Honba-no-Honmono https://honbamon.com/product/19-dojyo-hachiyakaki

Ichida-gaki

Provenance 18th Century. Unique features: discrete local variety. Other certifications: regional collective trademark.

Higashiizumo no Maruhata

Provenance 17th Century. Unique features: clay soil, no sulfur preservation, multi-story drying houses. Other certification: Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) – Honba-no-Honmono https://honbamon.com/product/28-maruhata-hoshigaki

Common steps toward industrialization:

Use of modern varieties; machine trimming of skin; mechanized massaging (tumbled); indoor temperature regulators; preservation with sulfur; drying chambers; electric fans; artificial twine for hanging; size-sorting machines

Critical discussion:

Of all the origin countries of dried persimmon, Japan stands out as having the best international reputation. Indeed, the lingua franca for persimmon in many countries is the Japanese word kaki (柿), including Russian, Ukrainian, German, Dutch, Tagalog, and others. Many varietals from Japan have been progressively integrated into agro-ecosystems in Europe, especially Eastern Europe and Spain, as well as the United States.

Our research has found an increasingly bifurcated market for hoshigaki, in which historical production areas in Japan have either (a) industrialized and reduced price to around 1 USD per unit (Ichida-gaki), or (b) have maintained labor-intensive practices, while allowing prices to reach 3-6 USD per unit (Doji Hachiya-gaki; Maruhata kaki; Noto Shika Koro-gaki). Representing something of a compromise is the Koro-gaki, which specifies only one labor-intensive practice (hand-massaging) and is often priced on the lower-end of the elite group around 3 USD.

With few exceptions, labor intensive practices are indeed associated with more refined quality. In particular, hand massaging has been observed to increase tenderness, create a consistent texture, and encourage sugars to accumulate on the exterior (the iconic white dusting on hoshigaki). The least invasive technological change is the use of machine trimmers, as only aesthetic dimensions are impacted. Some technologies impact the health or ecological dimensions, such as use of sulfur preservatives and use of artificial twines for hanging. Lastly, technologies employed to facilitate drying, such as drying chambers, indoor temperature regulators, and fans, can actually increase quality consistency but generally imply additional environmental impacts from energy use. A final contribution of technology has been in grading or sorting size to facilitate price differentiation; this allows additional market segmentation.

The long-term sustainability of the elite kaki varieties is increasingly precarious. Even mobilizing sufficient labor for only one of the labor-intensive practices – hand massaging – will become increasingly challenging as rural areas depopulate. The silver lining is that massaging persimmons is not a physically demanding activity, and elderly people can readily contribute to this endeavor long after they are unable to physically work in orchards.

Lastly, demand for hoshigaki is declining in Japan. Young people often stereotype hoshigaki as a treat mostly appreciated by older generations and are discouraged by the exaggerated price of the highly-reputed products. Likely, products like Ichida-gaki help to maintain a less costly entrance point for newer consumers, but it is unclear if the expensive varieties will become anything but gifts. It is also unclear if value-added production, such as processed treats made with hoshigaki, encourage or discourage the future consumption of hoshigaki, as many subtle organoleptic properties that are unique to simple hoshigaki are easily lost during processing.

Dry-houses in Ichida, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. This mountain valley district has an ideal climate for processing persimmons into hoshigaki but the scale of production has outgrown the capacity of traditional wooden dry-houses. Ryo Murakami

Wooden dry-house in Shika, Noto Peninsula, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. The climate in this region is mild, but often requires a bit more care in creating the ideal conditions for drying hoshigaki. These traditional houses allow wind and temperature to be controlled. Anastasiya Shtaltovna

Freshly-peeled persimmons in Shika, Noto Peninsula, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. Although this region maintains many traditional processing practices, they believe that machine peelers have become even more precise than manual peeling. The shape becomes more uniform. Hart Feuer

Kaki drying under controlled conditions. Producers are increasingly looking for ways to standardize their production and produce a more consistent and aesthetically pleasing product. The details of the such aesthetics are often lost on younger generations. Hart Feuer

The culinary artform of drying persimmons is so labor intensive that producers have consistently searched for ways to economize processing while maintaining quality. Sometimes, compromises are made.

Hand-massaging hoshigaki in Shika, Noto Peninsula, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. One of the most labor-intensive practices for ensuring even drying and consistent texture is massaging the fruit. To retain a pleasing aesthetic, this must be delicately carried out by hand. Anastasiya Shtaltovna

Hoshigaki “massaging” drums in Ichida, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. In some regions, the labor and cost of hand-massaging is considered to be too high. To achieve more consistent texture, while sacrificing aesthetic appeal, some producers use these drums to texturize the persimmons. Anastasiya Shtaltovna

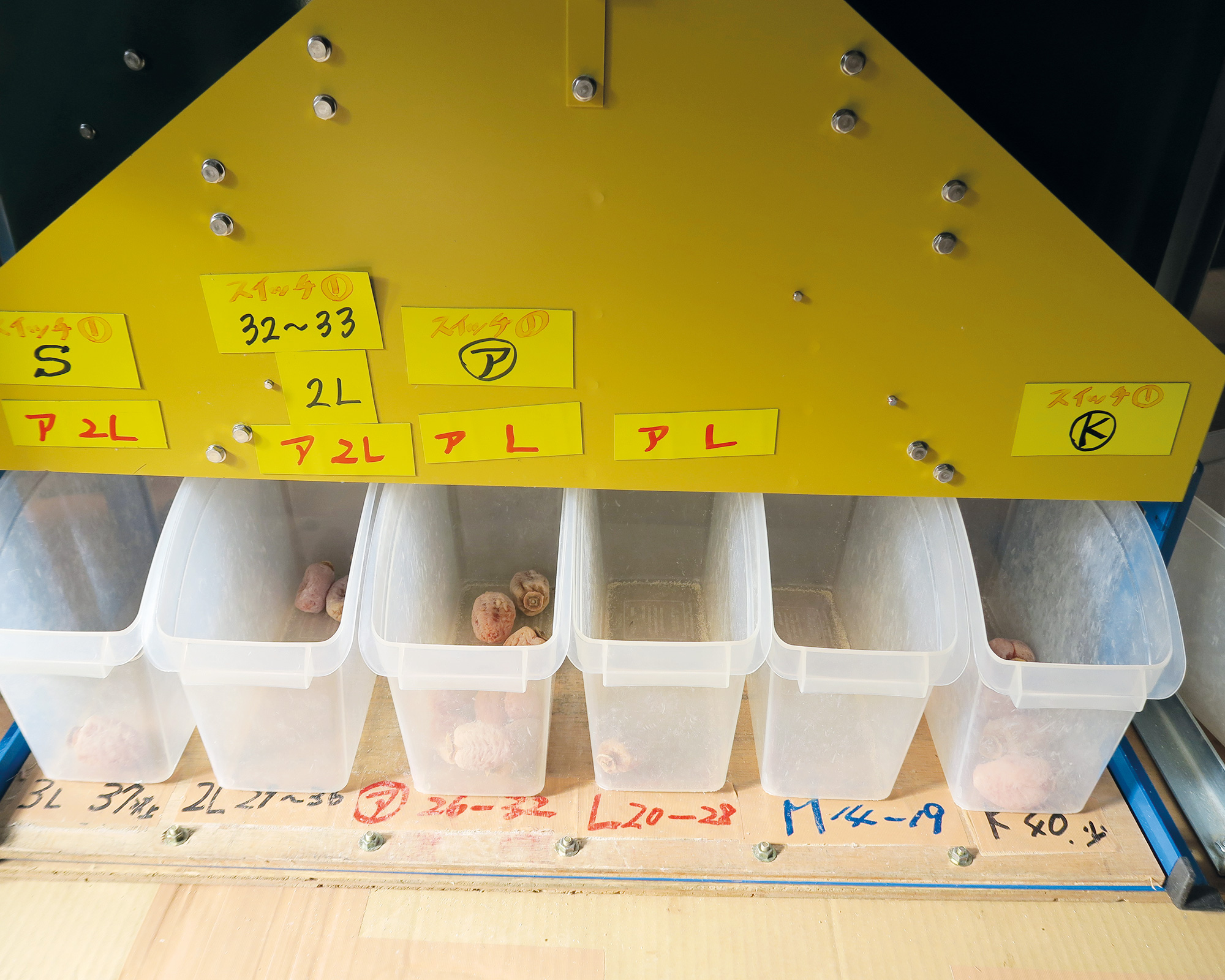

Sorting of hoshigaki. Although geographical indication can provide a baseline signal of quality, within regions and within the same farm, a wide range of quality can be found. Anastasiya Shtaltovna

Caption would be good early 18th Century. Unique features: discrete local variety, hand-cut, hand-massaged, swung to extract more sugar. Other certification: Protected Designation of Origin

Persimmon drying machine in Shika, Noto Peninsula, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. Producers are always trying to extend the shelf-life of hoshigaki, which has a notoriously short season. Reducing opportunity for decay can be encouraged by quick-drying in machines such as this. Hart Feuer

Information display about geographical indication in Ichida, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. As the place-of-origin certification and logo only appeared in 2016, many producer associations still actively educate consumers about the meaning of the logo. Hart Feuer

Conflicts and Challenges:

- The newest MAFF GI appears less valuable to elite products that have already invested heavily into their reputation using other mechanisms.

- The national-level reputation of Japanese hoshigaki is rooted in images of labor-intensive and precision care, including cultivation, trimming, massaging fruit, and the aesthetic of natural wind dried persimmons. These aspects are not consistently represented in the group of four hoshigaki from Japan, creating divergence between popular imagery and actual production methods.

- Young people are not being actively cultivated as future consumers.

- Processed foods made from hoshigaki, which are increasingly popular, devalue the subtle texture, aesthetic, and organoleptic properties of the original product.

Further reading

2020

‘Geographical indications out of context and in vogue: the awkward embrace of European heritage agricultural protections in Asia’, Feuer, H.N., Geographical Indication and Global Agri-Food: Development and Democratization, Bonanno, A., Sekine, K., Feuer, H.N. (eds). London: Routledge, pp. 39-53. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429470905

Open Access

PDF

2018

‘Geographical indication and development plans in South Korea: a study on dried Persimmons’, Hye Jin Oh, Moon Su Park, Kye Joong Cho, Soo Im Choi, Hag Mo Kang & Hyun Kim, Forest Science and Technology, 14 (1): 41-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2018.1425161

Open Access

PDF

Division of Natural Resource Economics,

Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, © Hart N. Feuer

Get in touch

info@heritagefoodliteracy.com