Globalization is an opportunity to cultivate caretakers of food heritage, if we are able to do it respectfully and effectively. The best initiatives won’t be museums, neither will they be hyper-global commodities. In our work, we explore two of the most promising and most troubled movements taking over the world.

Ulam

Wild Edible Plants

We study how to respectfully integrate wild plants into modern cuisines in order to protect biodiversity and attract young people. Our activities in this area consider wild plant food design, community and individual biodiversity conservation, and a regional training center to inspire and help young people rediscover wild foods.

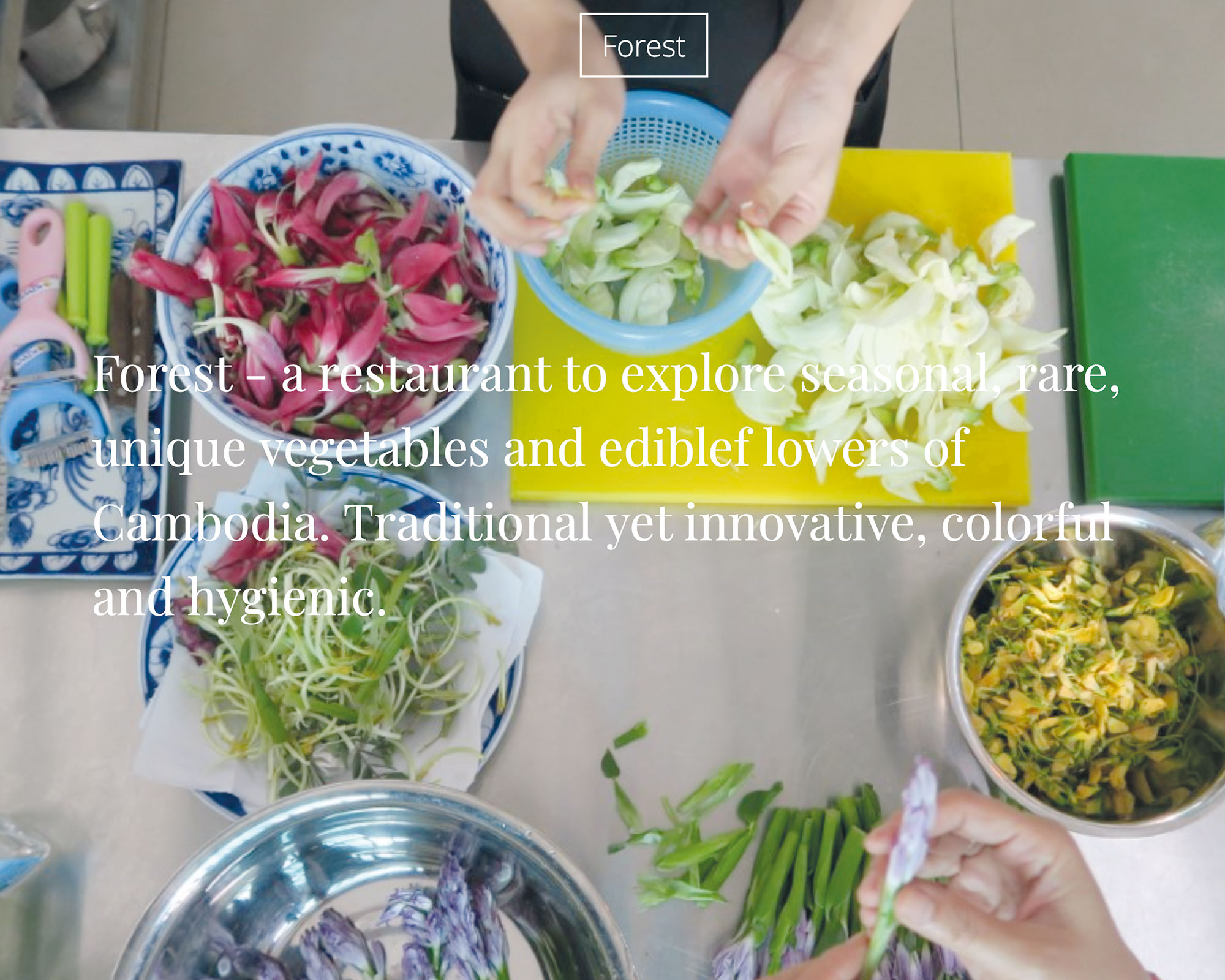

Forest pop-up

restaurant

With the right partners, a small restaurant can serve as a unique place for experimentation and research into future food patterns. We serve wild plant based foods and studied how they could keep a modern Cambodian cuisine biodiverse.

Ulam

School

Centered around the idea of deeper knowledge of, and interaction with, wild foods in each person’s own environment, the Ulam School seeks to use food education to proactively encourage new generations’ interest in healthy and culturally important indigenous plants.

‘Wild Gardens’ of

Southeast Asia

Challenging the notion that gardens are pristine spaces filled with conventional global crops, we are encouraging diverse gardens of indigenous plants that are low-maintenance, fit local cuisine, and provide many medicinal benefits. Sary Seng

Geographical

Indication (GI)

These days, there are a range of policies for governments and the private sector to give legitimacy to local food producers to help them protect and promote their own agri-food heritage both domestically and at the world stage. Local producers and civil society also have great ideas about how to accomplish this, too. We treat local and international ideas with the same respect. While we understand the potential of global marking, we also accept there are some foods that will be best appreciated in their historical food system. Therefore, we use like to use the term geo

Japan vs. Cambodia

While Japanese cuisine is famous for a few signature dishes, most of its agri-food heritage is buried in local districts and rarely encountered outside of the region. Cambodian cuisine is virtually unknown to the global public, but recent economic prosperity has raised awareness. What can we learn from the successes and mistakes of both a rich country with a well-known cuisine and a poor country with an unfamiliar cuisine?

Case Studies

(Japan and Cambodia)

Japan

Hatcho Miso

(Okazaki, Aichi)

Miso has historically been home-made, so few commercial producers can rival the almost unbroken lineage of Hatcho Miso, which has been produced in the same place for nearly 700 years. Hart Feuer

read more

Mikawa Mirin

(Aichi)

Once an essential household ingredient and flavorful alcoholic drink, mirin production has declined in recent decades. Some regions with more than 200 years of history are holding on to traditional, high-quality production practices. Hart Feuer

read more

In a high mountain valley bursting with persimmon trees, but lacking in labor, the Ichida region has tried to find a balance between mechanization and quality, while building up their marketing through tourism and food certifications. Anastasiya Shtaltovna

With unique fruit varieties and mild marine climate, the Noto peninsula has a long history of persimmons. Farmer-producers have mobilized to keep alive the age-old tradition of hand-massaging persimmons as they dry to maintain a luscious texture. Anastasiya Shtaltovna

Yamanashi Wine

(Kyoto)

Once a region famous for low-quality bulk wines, the region has incrementally enhanced its reputation for fruit and capitalized on its legacy of grape production to encourage a new form of wine tourism in Tokyo’s back yard. Hart Feuer

read more

Matsusaka Wagyu

(Mie)

Although not as well known internationally as its neighbor in Kobe, this beef production region has a renowned reputation within Japan. It is home to many unique animal welfare and fattening practices, and encourages collaboration with rice farmers. Kae Sekine

read more

Cambodia

Pursat Orange (Pursat/Battambang)

On the border of territory annexed by Siam (Thailand) in the 18th Century and returned to Cambodia under the French protectorate, these oranges have been at the intersection of political conflict and colonial intervention for nearly 100 years. Hart Feuer

read more

Pomelo

(Koh Trung)

Having discovered a unique micro-climate on a Mekong River island surrounded by fresh-water dolphin habitat, farmers in Koh Trung have cultivated a unique variety of pomelo in a serene eco-tourism environment. Hart Feuer

read more

Palm Sugar

(Kompong Speu)

Everyone in Cambodia agrees that the soils in parts of Kompong Speu province are ideal for Palmyra sugar palm trees. A daring method of climbing these tall trees to collect sap and infusing with aromatic wood has made the sugar regionally famous. Hart Feuer

read more

Pepper

(Kampot)

Already well-known before the French colonial period, Kampot pepper became synonymous for the best quality spice from Southeast Asia. Its mild sharpness and floral character stand out. Sary Seng

read more

Palm Beer

(Kandal)

Still primarily a cottage industry, sugar palm beer (tnot chu) is only slowly being commercialized. Consumers are confused to find neatly bottled beer instead of refilled plastic Coca Cola bottles. Hart Feuer

read more

Nem Fish Paste (Battambang)

A unique method for fermenting and conserving fish with spicy chilis has made Battambang famous for travelers seeking a hearty snack. Traditional packaging has been cast off for hygiene and more modernization threatens this traditional practice. Sary Seng

read more

Division of Natural Resource Economics,

Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, © Hart N. Feuer

Get in touch

info@heritagefoodliteracy.com